Sulfur is used in agriculture because it supports core plant functions that directly affect yield, quality, and nutrient efficiency. While nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium often dominate fertilization programs, sulfur is a critical building block in amino acids and proteins and plays an important role in photosynthesis-related processes. When sulfur is limited, crops may not use applied nitrogen efficiently, which can lead to weaker growth and lower product quality even when other nutrients appear adequate.

This article explains why Sulfur Is Used in Agriculture, what it does inside the plant, how it influences soil conditions (including realistic expectations for PH management), and how to recognize sulfur deficiency without confusing it with similar nutrient issues. It also provides practical guidance on choosing the right sulfur form and application approach, plus a concise decision framework and common mistakes to avoid. For background about our organization, you can visit Farazoil.

Disclosure: Farazoil supplies sulfur products. This article is educational and does not replace local agronomic advice.

Practical note: Nutrient response depends on soil type, irrigation/rainfall, yield target, and existing sulfur supply. Confirm decisions with soil and/or tissue testing where feasible.

Key takeaways:

- Sulfur is essential for protein formation (cysteine and methionine) and supports efficient growth.

- Balanced sulfur improves nitrogen use efficiency and reduces “wasted” nitrogen response.

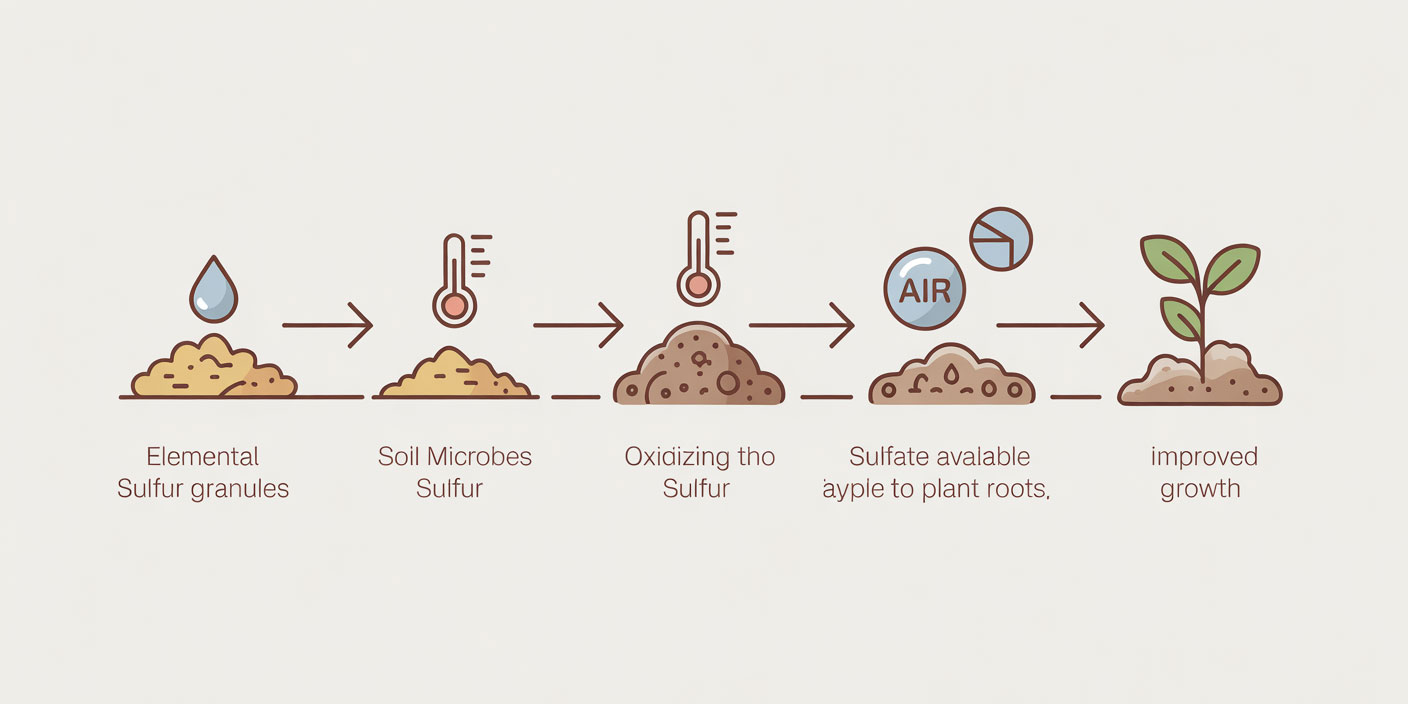

- Sulfate is plant-available immediately; elemental sulfur must oxidize first and works more slowly.

- Sulfur deficiency often appears first on younger leaves, unlike nitrogen deficiency which typically starts on older leaves.

- In alkaline/calcareous soils, pH change from elemental sulfur is gradual and limited by buffering.

What Sulfur Does in Crops (and Why It Matters More Than Many Think)

Sulfur is not a “nice-to-have” nutrient. It is one of the essential elements plants require to complete basic growth and production processes. In practical terms, sulfur affects how well a crop can convert nutrients into biomass, grain, oil, or marketable quality. When sulfur is inadequate, growth can stall even if nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are supplied correctly—because the plant cannot finish key biochemical steps without enough sulfur.

Sulfur’s role in amino acids and proteins

A major reason sulfur matters is that it is a structural component of sulfur-containing amino acids—especially cysteine and methionine—which are used to build proteins. Proteins are not only “plant tissue”; they also form enzymes and functional compounds that regulate metabolism and development. If sulfur is deficient, protein formation is constrained, and crops may show reduced vigor and poorer quality, particularly where protein content or strong vegetative growth is important.

Relationship with chlorophyll formation and photosynthesis

Sulfur also supports processes linked to chlorophyll formation and photosynthesis. While sulfur is not chlorophyll itself, it contributes to the plant’s ability to produce and maintain the compounds and enzymes involved in photosynthetic activity. When sulfur is sufficient, plants generally maintain stronger green color and more stable growth because energy production and carbon assimilation run more efficiently. When sulfur is limited, plants often show paler growth and reduced development—especially in actively growing tissues.

Impact on oil and protein quality (oilseeds, cereals, and forages)

Sulfur is closely tied to quality outcomes, not only yield. In oilseed crops, adequate sulfur supports the biochemical pathways involved in oil formation, which is one reason sulfur management is commonly emphasized in those systems. In cereals, sulfur can influence grain quality characteristics associated with protein composition. In forage crops, sulfur contributes to protein formation and can affect feed nutritive value—making it relevant for livestock-oriented production where forage quality is a primary economic driver.

The Main Reasons Sulfur Is Used in Agriculture

Sulfur is used in agriculture for three practical reasons: it supports plant growth and quality as a core nutrient, it improves the efficiency of other nutrients (especially nitrogen), and it can be part of a longer-term soil management strategy in specific conditions.

Improving nitrogen use efficiency (the N–S relationship)

Nitrogen drives vegetative growth, but plants need sulfur to convert that growth into true productivity—especially protein formation. When sulfur is limiting, crops may absorb nitrogen yet struggle to fully utilize it, which can show up as weaker growth, lower protein quality, and disappointing results despite adequate nitrogen inputs. Balanced sulfur nutrition helps crops turn nitrogen into yield and quality more consistently.

Supporting yield and produce quality

Sulfur’s influence is not only “more biomass.” It is closely tied to quality metrics such as protein composition and oil formation (in oilseeds) as well as overall crop uniformity. In many systems, correcting sulfur limitation is less about a dramatic visual change and more about improved performance and a better return on the overall fertility program.

Strengthening resilience under stress (with realistic expectations)

Sulfur contributes to the formation of compounds involved in plant defense and stress response. In practice, this means adequate sulfur nutrition can support a crop’s ability to cope with stressors. However, sulfur is not a substitute for integrated pest management or sound agronomy. The most dependable benefit remains nutritional: healthy crops generally resist stress better than nutritionally constrained crops.

Sulfur and Soil Chemistry — pH, Availability, and When “Acidifying” Is Real

Soil chemistry is one of the most misunderstood areas of sulfur use. Sulfur can influence soil PH, but the outcome depends on the sulfur form, the soil’s buffering capacity, and environmental conditions.

Elemental sulfur oxidation (what must happen first)

Elemental sulfur (S⁰) is not directly usable by plants. It must be oxidized by soil microorganisms into sulfate (SO₄²⁻). This conversion produces acidity, which is why elemental sulfur is discussed as a tool for lowering PH. The key point is timing: the PH effect is not immediate.

What controls the speed of conversion

The oxidation rate depends on:

- Moisture: microbes need adequate moisture to function.

- Temperature: warmer conditions generally accelerate microbial activity.

- Particle size: smaller particles provide more surface area for microbes.

- Microbial activity and soil aeration: healthy biological activity improves conversion.

Because these variables differ widely, “how fast it works” is not a fixed rule—it is context-dependent.

Alkaline soils: realistic expectations and limitations

In alkaline or calcareous soils, lowering PH is often more challenging than many expect. Elemental sulfur can support PH management, but results may be gradual and localized, and soils with strong buffering (high carbonate content) can resist PH change. In these settings, sulfur is best framed as one component of a broader soil strategy rather than a single-step fix.

Clearing common misconceptions (gypsum vs elemental sulfur)

A common confusion is treating all sulfur-containing materials as “acidifying.” For example:

- Gypsum (calcium sulfate) supplies sulfate sulfur and calcium, but it is not the same as elemental sulfur for PH reduction.

- Elemental sulfur is the form associated with acidification potential (after oxidation).

Understanding this difference prevents wasted applications and unrealistic expectations.

Forms of Sulfur Used in Farming — Elemental vs Sulfate (and Product Formats)

Choosing the right sulfur form is mostly about your objective: quick nutrition correction versus slower, longer-term supply and soil strategy.

Sulfate sources (fast availability): typical use cases

Sulfate is the form plants absorb. Sulfate-based inputs are typically preferred when:

- a crop needs sulfur quickly.

- a deficiency is likely during the season.

- you want more predictable short-term availability.

Common sulfate-containing materials include ammonium sulfate, potassium sulfate, magnesium sulfate, and gypsum (depending on your agronomic goal).

Elemental sulfur (slow release): typical use cases

Elemental sulfur is often chosen when:

- you want a gradual sulfur supply (as it converts to sulfate)

- you are planning a longer-term sulfur program

- PH management is part of the strategy (with realistic expectations)

Because it requires microbial conversion, elemental sulfur is generally planned earlier in the season or ahead of the crop’s peak sulfur demand.

Quick comparison: elemental sulfur vs common sulfate sources

| Source | Plant availability speed | Primary use | PH effect |

| Elemental sulfur (S⁰) | Slow (requires microbial oxidation) | Longer-term sulfur supply; part of PH strategy | Acidifying potential after oxidation |

| Ammonium sulfate | Fast | Rapid correction + nitrogen supply | Can be acidifying over time |

| Gypsum (calcium sulfate) | Fast (sulfate) | S + calcium supply; soil structure/sodicity contexts | Generally, not used to lower pH like elemental sulfur |

| Potassium sulfate | Fast | S + potassium where chloride sensitivity matters | Typically, minimal direct pH effect |

| Magnesium sulfate | Fast | S + magnesium support (specific deficiencies) | Typically, minimal direct pH effect |

Granular formats: practical handling and field uniformity

In many operations, product format matters as much as chemistry. Granular products can support:

- consistent spreading and distribution

- easier storage and transport

- improved handling in broad-acre application systems

If you are reviewing product format options, see Granular Sulfur for a dedicated overview.

Compatibility notes (Mixing, Storage, and Safety basics)

- Avoid assuming all products blend cleanly; physical compatibility can vary by granule size and density.

- Store sulfur products dry and handle dust responsibly.

- Align the product choice with your equipment (spreader type, placement capability, irrigation system compatibility, etc.).

Sulfur Deficiency — Symptoms, High-Risk Conditions, and How to Confirm

Sulfur deficiency is often missed because it can resemble other nutrient problems. Accurate identification protects yield and prevents unnecessary inputs.

Visual symptoms and how they differ from nitrogen deficiency

Sulfur deficiency commonly appears as:

- pale green to yellowing (chlorosis)

- reduced growth and thin stands

- weaker overall vigor

A useful distinction:

- Sulfur deficiency often shows first on younger leaves (lower mobility in the plant)

- Nitrogen deficiency more often appears first on older leaves

This is not a perfect diagnostic rule, but it is a practical starting point.

High-risk soils and conditions

Deficiency risk increases when:

- soils are sandy or low in organic matter.

- sulfate is prone to leaching under rainfall or heavy irrigation.

- yield levels are high, increasing nutrient removal.

- fertility programs have reduced sulfur-containing inputs over time.

Soil test vs tissue test: what each tells you

- Soil testing helps estimate sulfur supply potential and leaching risk.

- Tissue testing helps confirm what the plant is actually taking up.

When symptoms are present but ambiguous, tissue analysis can reduce guesswork and guide corrective action.

How to Apply Sulfur — Methods, Timing, and Practical Field Scenarios

Application method should match the crop’s demand window, the sulfur form, and your field constraints.

Pre-plant soil application vs in-season correction

- Pre-plant programs are often better for elemental sulfur because conversion takes time.

- In-season correction usually favors sulfate sources because the plant can use them immediately.

Broadcasting vs banding: decision considerations

- Broadcasting supports uniform distribution across the soil surface/zone, common in broad-acre systems.

- Banding/placement can improve efficiency in some soils and crops by positioning nutrients closer to roots.

The best choice depends on crop type, soil texture, moisture regime, and equipment.

Foliar sulfur: when it helps and when it’s the wrong tool

Foliar applications can be useful for targeted, short-term support, especially when root uptake is limited. However, foliar sulfur is generally not the most efficient way to supply large seasonal sulfur needs. If sulfur demand is substantial, a soil-based program is typically more effective.

Irrigation/fertigation considerations (high-level)

Where fertigation is used, sulfate forms can be integrated more easily than elemental sulfur. Water chemistry and system compatibility matter; a program should be aligned with irrigation design and local agronomic practice.

How Much Sulfur Do Crops Typically Need? (A Practical, Test-Driven Way to Think About Rates)

There is no single sulfur rate that fits all farms. The right program depends on how much sulfur the crop is likely to require during the season and how much the soil and water can realistically supply.

What most strongly determines sulfur requirement

- Yield target: higher yields remove more sulfur and increase the chance of response.

- Soil organic matter: low organic matter soils often supply less plant-available sulfur.

- Soil texture and leaching risk: sandy soils and heavy irrigation/rainfall increase sulfate loss.

- Irrigation water sulfur: some water sources contribute meaningful sulfate sulfur.

- Crop type: oilseeds and high-protein crops tend to be more sensitive to sulfur limitation.

A simple decision guide (without guessing numbers)

- Low response likelihood: heavier soils, moderate organic matter, limited leaching, and no history of deficiency.

- Medium response likelihood: mixed soils or moderate leaching risk, high yield target, reduced sulfur inputs in recent years.

- High response likelihood: sandy/low organic matter soils, heavy irrigation/rainfall, visible symptoms, or confirmed low sulfur in soil/tissue tests.

Best practice

Use soil testing to understand sulfur supply potential and leaching risk, and tissue testing to confirm actual uptake. If you need fast correction, prioritize sulfate sources; if you are building longer-term supply and considering gradual PH influence, plan elemental sulfur earlier.

Practical Decision Framework — Choosing the Right Sulfur Strategy

Use this framework to choose a sulfur approach based on your objective and risk level.

If the goal is rapid correction of deficiency

Choose a sulfate source and align timing with the crop’s immediate growth needs. Confirm deficiency risk (or diagnosis) using symptoms plus soil/tissue data where possible.

If the goal is soil PH management over time

Consider elemental sulfur as part of a longer-term plan, with the expectation that conversion and PH impact take time and vary with soil conditions. Treat it as a soil strategy tool, not a quick fix.

If the goal is improving nitrogen efficiency and crop quality

Build sulfur into the baseline fertility plan so nitrogen is not “left unused” due to sulfur limitation. This is particularly relevant in high-yield systems and crops where protein/oil quality matters.

Quick checklist before application

- Do you have soil and/or tissue data indicating a likely response?

- Is your goal fast nutrition or long-term supply/PH strategy?

- Is your soil prone to leaching (sandy, low organic matter)?

- Do your equipment and timing allow correct placement and uniform distribution?

- Are you avoiding common misreads (e.g., confusing N vs S deficiency)?

Common Mistakes and Troubleshooting

Correct sulfur management is often less about “adding more” and more about avoiding predictable errors.

Expecting immediate pH change from elemental sulfur

Elemental sulfur needs microbial oxidation. If you apply it and expect an immediate PH shift, you may conclude it “didn’t work” when the real issue is timing or conditions limiting conversion.

Over-application and nutrient imbalance

More is not always better. Excessive application can create imbalances, unnecessary cost, and potential soil chemistry issues in sensitive contexts. A test-driven program reduces this risk.

Ignoring soil buffering and water management realities

Highly buffered soils can resist pH change. Likewise, heavy irrigation can leach sulfate, changing how long sulfur remains available. Program design must reflect these realities.

Misreading deficiency symptoms

Sulfur deficiency can be confused with nitrogen or other issues. When the financial or yield stakes are high, confirmation through testing is often worth the effort.

Conclusion

Sulfur is used in agriculture because it is essential for protein formation and key growth functions, it helps crops utilize nitrogen efficiently, and it can support soil management strategies—particularly where sulfur supply is limited or where soil chemistry constraints reduce nutrient performance. The most effective sulfur programs match the sulfur form and application method to the objective: sulfate sources for faster correction, elemental sulfur for gradual supply and longer-term strategy.

If you suspect sulfur is limiting your crop’s performance, avoid guessing. Start with symptoms as a clue, then confirm risk through soil and/or tissue testing, and select a sulfur approach that fits your crop, soil conditions, and timing window.

FAQ

Is sulfur a macronutrient or a micronutrient?

Sulfur is an essential plant nutrient commonly classified as a secondary macronutrient (alongside calcium and magnesium). It is required in larger amounts than micronutrients.

Why do sulfur deficiency symptoms look like nitrogen deficiency?

Both sulfur and nitrogen are tied to chlorophyll-related processes and overall growth, so deficiencies can look similar. A practical difference is that sulfur deficiency often appears first on younger leaves.

Elemental sulfur vs sulfate: which works faster for plants?

Sulfate works faster because it is the form plants absorb. Elemental sulfur must be converted into sulfate first, so it is slower and more dependent on soil conditions.

Can sulfur lower soil pH in alkaline soils?

Elemental sulfur can contribute to pH reduction over time, but results vary with soil buffering capacity, moisture, temperature, and microbial activity. In strongly buffered soils, expectations should be conservative.

When should sulfur be applied: pre-plant or in-season?

Both can work. Elemental sulfur is often planned pre-plant due to conversion time. Sulfate sources are more suitable for in-season correction when immediate availability is needed.

Is foliar sulfur a replacement for soil application?

Usually not. Foliar sulfur may help short-term support, but it typically cannot supply the full seasonal sulfur requirement in systems with substantial demand.

How can I avoid applying too much sulfur?

Base decisions on soil and tissue testing where feasible, match the form to the goal, and avoid applying “just in case” without evidence of likely response.

Meta Description Options

Discover why Sulfur Is Used in Agriculture: crop functions, soil chemistry, deficiency diagnosis, and best practices for choosing elemental vs sulfate sulfur.